W.G. Sebald & memory

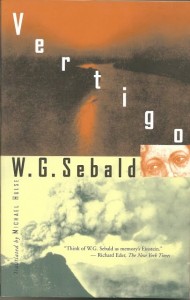

“Think of W.G. Sebald as memory’s Einstein,” says The New York Times’ Richard Eder on the cover of Sebald’s first novel, “Vertigo.”

“Think of W.G. Sebald as memory’s Einstein,” says The New York Times’ Richard Eder on the cover of Sebald’s first novel, “Vertigo.”

This statement feels true when you imagine the “quantum Einstein,” the one grasping for form in dark spaces, or, the measurer who’s instruments fail him. “Vertigo” may not be Sebald’s best novel, but it announces his style of unreliable narration in the person of a narrator greatly concerned about reliability and context.

If you haven’t read it, here’s the basic “action” generated in the novel: A man travels through northern Italy and over the border into Austria musing about things like Stendhal’s service in Napolean’s army, the historical background of the regions he passes through and Kafka’s similar journey shortly before his death. Seven years later, the narrator repeats the very same itinerary, curious about his disturbed state of mind during the first trip but also in search of what might have eluded him.

What are readers to make of a narrator who can’t speak directly about what is tormenting him, or who spends a chapter retracing the travels of the Kafka-like “Dr. K.”? As if they were pieces of evidence, there’s a black-and-white snapshot of Kafka with friends on one page, and on another a photo of an Italian street crowd allegedly awaiting the arrival of the “Deputy Secretary of Insurance from Prague” (mimicking Kafka’s real-life occupation). He’s a narrator for whom the past is full of curved spaces. Born into 1944 Germany, Sebald often writes as if he’s so haunted by his own country’s history that he is forced to adopt the histories of others.

In the first chapter of “Vertigo,” Stendhal is quoted writing that “even when the images supplied by memory are true to life one can place little confidence in them.” As proof, he recalls a glorious descent down an Italian mountain pass during his service in the Napoleonic Wars, particularly the entrance into the town of Ivrea as the sun set. Years afterward, he realizes looking through newspapers that the picture of the town he had in mind was actually from an engraving.

If history could be as vulnerable as memory, it would be easier for Sebald’s narrator to escape it. And that would mean a denial of everything, including the present, in order to live in a fantasy. Whether he’s employing cheesy old photographs or leading us through labryinths, Sebald never makes that choice. Just because we possess inadequate instruments does not mean we stop measuring.